Chapter 14 : Stakeholder Engagement

14.1 Stakeholders as Partners

14.2 The Pitfalls

14.3 Need for Gauging Stakeholder Importance

14.4 Disclosure of Who Decides

14.5 Stakeholders as Supporters

14.6 Reservoir Association Establishment

14.7 Reservoir Association Structure

14.8 Reservoir Association Projects

14.1 Stakeholders as Partners

Many habitat management issues usually involve public resources, so the general public and various organizations have a vested interest in the outcomes of decisions. Natural resources also have multiple uses that can lead to competition among user groups and potentially conflict among groups. By implementing a stakeholder- driven process, managers can help those with vested interests understand how decisions are arrived at and participate in the decision-making process.

Stakeholders are defined here as groups, organizations, or individuals with some level of vested interest (Watt 2014) in the effects of fish habitat management. These groups generally include consumers (e.g., anglers, boaters, citizens interested in natural resources, lake associations); nongovernmental organizations (e.g., Bass Anglers Sportsman Society, The Nature Conservancy); natural resource management agencies (e.g., state or federal agencies charged with managing some aspect of a reservoir resource); political representatives, elected or appointed, to local, state, or federal governments; and economic interests such as local business or landowners potentially affected by activities associated with a reservoir. This list can change or shift in emphasis depending on the nature of habitat alteration. For example, changes to water regime may be of interest to a different set of stakeholders than installation of reefs and structures.

Stakeholders can be a vital part of the process of identifying management goals. While often it is possible to anticipate and identify goals without including stakeholders, involving them will typically assure a more comprehensive analysis of goals and also will help managers anticipate and, possibly, resolve or at least minimize potential conflicts among competing user groups. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, participation builds public support and ownership of the decision when the public is explicitly involved in the decision-making process (Watt 2014).

Back to the Top

14.2 The Pitfalls

Working with stakeholders can involve controversy as different stakeholders may have different objectives (Townsley 1998). Often stakeholders may be members of more than one group and, hence, are likely to have multiple objectives. For example, an angler with recreational objectives may also be a fishing guide or a bait-shop owner with economic objectives. Similarly, an agency staff member may also be an angler. The potential downside of including stakeholders with multiple group memberships is that a stakeholder may portray him or herself as representing one stakeholder group when many of his or her objectives may reflect the other group, which can lead to conflict. The benefit is that such an individual may facilitate communication and understanding among different stakeholder groups.

All stakeholders are not necessarily equal. For example, all decision makers are stakeholders in that they have a vested interest in the outcome of a management decision. However, not all stakeholders are decision makers. Decision makers often have the legal authority or accountability for carrying out a management action, such as providing funds or personnel and equipment. Thus, decision makers generally have greater responsibility and accountability than other stakeholders. So the question is, what stakeholders should be involved in the process and how much weight should the group be granted?

Back to the Top

14.3 Need for Gauging Stakeholder Importance

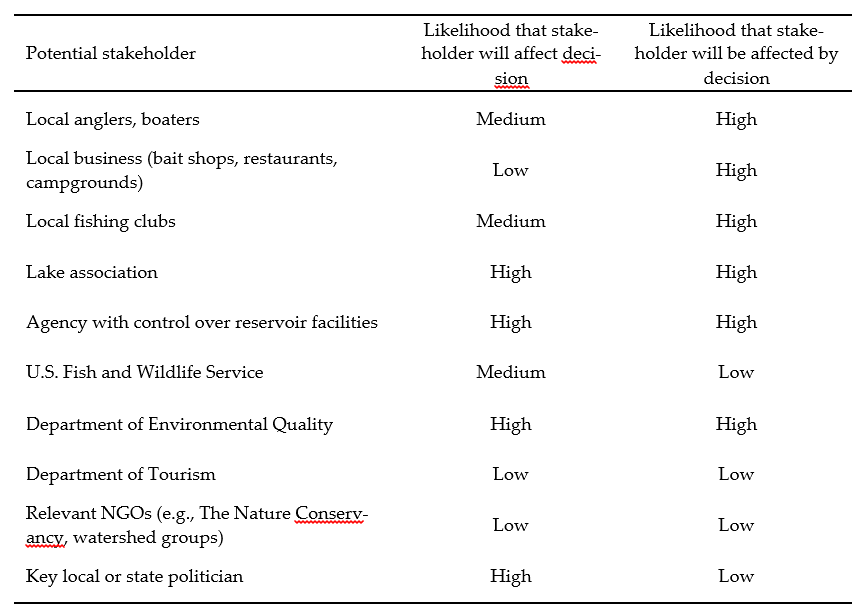

A preliminary stakeholder analysis may be used to prioritize people, groups of people, or organizations that significantly may influence or be influenced by the management decision. One approach is to develop a matrix to evaluate stakeholder importance (Freeman 2010). Potential stakeholders can be scored in a matrix based on the relevance of the potential management action to the stakeholder (i.e., likelihood that the stakeholder will be affected by a decision) and the perceived ability of the user to affect policy decisions (i.e., likelihood that the stakeholder will affect the decision) (Allen and Miranda 1997). Potential stakeholders that are strongly affected by a decision or have a strong effect on the decision are essential to involve in arriving at a decision. Conversely, it is not important to involve those that are not affected by the decision or have little or no influence on the decision.

The first step in creating such a matrix is to develop a list of potential stakeholders, including as many as possible without limiting the list to those initially perceived to be important. A useful set of questions one may ask to identify stakeholders might include (1) what groups potentially will be affected by the decision; (2) what groups often are involved in these decisions; (3) who has the knowledge of how the system works (e.g., biologists, engineers); (4) who has the legal authority to approve or implement management actions; and (5) who can potentially overturn the decision. Once the matrix is created, the rankings are examined to distinguish the stakeholders that are essential to involve in the decision-making process from those that are desirable (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1. Example stakeholder analysis matrix for a situation in which a state fishery conservation agency is considering sediment removal from a large arm of a reservoir as a way to improve fish habitat. To remove sediment, water level in the lake will be lowered for about 1 year. The matrix lists potential stakeholders and their likelihood of affecting or being affected by the sediment removal. Three groups ranked high on both counts, and four others ranked high on one count. These seven groups may be included as stakeholders and the others excluded or their input down-weighted. NGO = nongovernmental organization.

Back to the Top

14.4 Disclosure of Who Decides

Become a Contributing Sponsor

Become a part of projects that need your support.